Haves and Have Nots

Similar to the Victorian era, we live in an age of great social inequality, of haves and have nots. Fortunately these days, the State has certain obligations to its citizens to provide social welfare, although in England it has been cut back, reduced and generally made less available to the needy over recent years.

Going back in time

The Victorian era, in a similar way to the present, was a period of great change. By the end of the era, there had been significant advances in industrialisation, communications, and great innovations in science and technology. All of this brought great wealth to the country and the moneyed classes increased their fortunes.

But the poor often paid the price of these changes. The wealth generated in cities hastened an agricultural depression, with people flocking to increasingly urbanised areas where large houses were converted into overcrowded tenements, neglected by the landlords, and ending up as slums. In an age where there was little sanitisation, and long hours of manual and child labour were the norm, the poor were trapped and vulnerable to exploitation.

Victorian food

The needy

Richard Bentley – Heritage Auction Galleries, Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons.

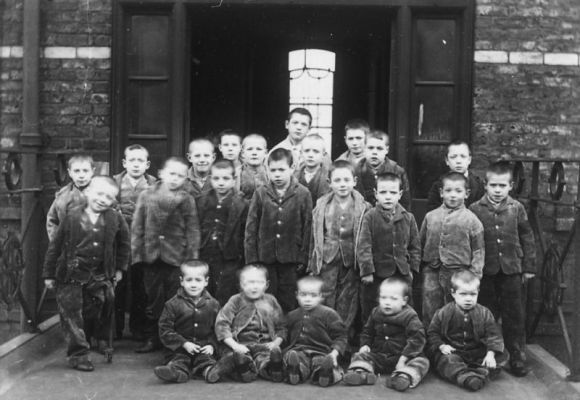

Unsurprisingly, what and how you ate in Victorian times depended on your financial status. At the bottom of the scale were the people in workhouses, who had no means of supporting themselves. In return for long hours of labour, the workhouses provided very basic food and shelter.

However, the conditions were often rough and undignified, and the workhouses often resembled prisons more than anything else. Charles Dickens’ harsh depiction of the workhouse and the brutal treatment of the inmates in Oliver Twist was in fact, a pretty realistic representation, intended to raise awareness of the unacceptable cruelties within the workhouse system.

Gruel – a cereal such as wheat or oats, boiled in water or milk- was a common breakfast in the workhouses . A version existed using only flour and water, so gruel could vary in consistency from porridge to……basically, slop. And Oliver Twist had the temerity to ask for more.

Lunch, known as dinner, varied from cooked or pickled meat with potatoes and vegetables in the best of cases to a watery broth in the worst scenario, The evening meal, called supper, was generally around 6pm and consisted of bread and broth, and maybe a small piece of cheese if you were lucky. The workhouse was not a solution for anything. Towards the end of the 19th century, the idea began to take root that the State should take some responsibility for the more vulnerable members of society.

The working class

The Victorians had a strict class system and even the working class was divided into three tiers – firstly manual labourers, followed by artisans, and the top level, the “educated working man”. Manual labourers, at the bottom of the hierarchy , were paid very low wages and could only afford very basic foodstuffs, let alone kitchen utensils.

One of the cheaper items on offer at the butchers’ was broxy, which referred to spoiled meat from animals which had died from disease. If you didn’t fancy food posioning or death from broxy, boiled or fried sheeps’ trotters were also a popular dish. Yes, I’m feeling queasy at this point as well….

Slum residents generally existed on a diet of bread, dripping, tea and broth. The worst off also ate potato peelings and rotten vegetables. Inevitably, this dreadful diet had effects on people’s health and harmed the healthy development of growing children.

The moneyed classes

With the invention of railways and better transport systems during the Victorian period, food produce could be transported more easily across the country, providing a better choice of fresh food for those who could afford it.

Although the middle classes could not afford to be as extravagant as the wealthy, the financially stable also had a variety of foods available to them. Meat, fish, cheese, eggs and bacon were staples along with porridge, and the traditional Sunday roast dinner. Meat was an expensive commodity so was generally out of reach for the less well off, although it could be substituted with offal, or a nice sheep or calf head. Eurgh. Please note I have spared you (and myself) the images.

Beyond Britain, Victorian cuisine had a reputation for being tasteless and unappetising , with all foodstuffs basically being boiled to death. This is justified to a certain extent, but there was also a trend towards culinary creativity. It goes without saying of course, that you would need to be wealthy in order to indulge this creative vein.

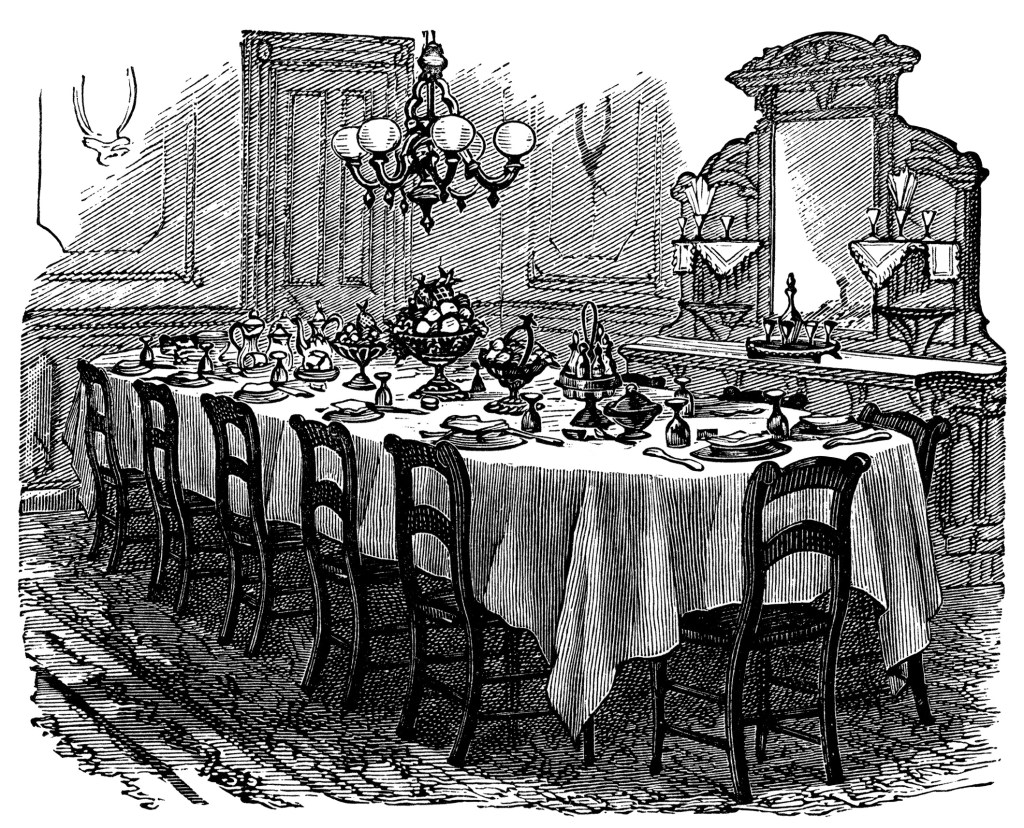

For the well-off, it became fashionable to host elaborate dinner parties, showing off expensive china and silverware and with highly decorated tables. The menus would generally consist of soup and fish as a starter, followed by meat or stew, game or poultry and conclude with dessert, cheese and liquor. Certainly there were no poisoned meats or rotten vegetables on offer in these fine displays of prosperity.

Large Victorian properties would possess huge kitchens including a scullery for cleaning and storing crockery and kitchen utensils, a pantry for food storage prior to use, and a larder for meat preparation as well as ample kitchen space for the actual cooking. . Not to mention the the members of staff employed to deal with all the culinary preparation of the menu.

It has been noted that upper and middle class women did sometimes join in with the menu preparation. Elizabeth Robins Pennell was an art-turned-food critic who considered that food could be a high form of art, and encouraged women to use their creative gifts rather than consider cooking to be a household chore.

Although we would be familiar with many of the foodstuffs that Victorians ate, there are several dishes that would definitely not appeal to modern tastes. An example of this is the Brown Windsor Soup, which sounds pretty sinister to me already. It was a concoction of meat in its gravy, vegetables, vinegar, dried fruit, and for those who could afford it, a dash of Madeira wine. Still not liking it? Me neither. But it was “reputed to have built the British Empire.” Yikes.

Although it was orginally a chef’s gourmet recipe, by the 1920’s poor old Windsor soup had became a synonym for the worst of English cuisine.

Other delights included bone marrow on toast, heron pudding, haggis, and a popular breakfast was kedgeree – an Anglo-Indian dish consisting of smoked haddock, rice, milk, hard-boiled eggs and seasoned with coriander, curry and/or turmeric. Those who could afford it believed in hearty breakfasts, but I think I’ll stick to my cup of coffee and piece of toast, thanks very much.

Photo By User:Justinc – Own work, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org

Victorian Food and Health

It is obvious that the abysmal quality of diet was detrimental to the poor and could even kill them. The rich however, did not suffer from the same diet-related problems as we do today.

For a start, convenience foods high in fat or sugar content were yet to be invented. The population was, on the whole, much more active than we are today. The Victorians ate plenty of seasonal vegetables and fruit due to the development of new transport systems. Their intake of nuts, whole grains and omega rich foods all meant that the chronic and degenerative diseases which are common in today’s society hardly existed. Diabetes type 2, for example, which is rife in our modern world, was practically non-existent.

What can we learn ?

Our modern society is generally aware, that with the rise of largely sedentary jobs, people who have access to plenty of food need to exercise and eat healthily to help ward off disease. And secondly, maybe we (and especially the 331 Members of Parliament that voted against a food supply for kids in need) should be a little more inclined to believe that poorer people may not have money to feed their children through no fault of their own. We may no longer suffer some of the barbaric incidents of the Victorian era, but the financial gap between the well-heeled and the less fortunate seems to be, very sadly, on the increase.

You must be logged in to post a comment.